Concorde Crew All At Sea

Introduction

This was written in 1991 for the British Airline Pilots’ Log magazine, for airline colleagues as a glimpse of other ways to fly. Today, television documentaries using historical footage of carrier operations seem to be airing non-stop. Our visit 30 years ago was a privileged invitation to one Concorde flight crew by Vice Admiral Jack Ready, commander of the US Naval Air Force Atlantic, that’s one half of this nation’s carrier fleet. Jack, a pilot’s pilot by all accounts, likened the Concorde’s steady but relentless accelerate to Mach 2 to the F4 Phantom, but the subsequent two hour cruise at that speed without afterburner or refuelling was something special: a good idea for his aircraft, in the future, maybe.

A TWO-DAY TRIP TO THE USS DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER

The Boat

“Write what you know.” they say.

It’s easier when you get older; more to write about. But there comes a specific time when your pen frees itself, you really don’t care about what anyone thinks about what you have to say. You write it anyway. Is this the rage Dylan Thomas talks about? The start of a determination to go down fighting? Maybe; you’ve little to lose.

This is mid-life: a popular subject before 70 became the new 40. Crisis is a bit heavy. It’s more an awareness that the uphill part is over, and it’s downhill from here; a looking back on how you made your way up to the plateau, and, perhaps, an acknowledgement of feelings of resentment and regret at the straight and unenterprising nature of your climb. Of course you were unable to choose your starting point, and were content to be carried along with the crowd, taking the easy options, unaware of what lay behind rocky side-turnings and closed doors; lacking the gumption to decide for oneself. Well, you didn’t realise, did you, brought up on ‘children should be seen and not heard.’ What dismally stunted imagination is it that says ‘ If I had my time over again I wouldn’t change anything.’ Is this a measure of real happiness? For some, perhaps, but not everyone.

I got a glance through one of those side-doors recently. Some of my friends used to fly fighters off aircraft carriers. I envy them. For those who feel at home in an aeroplane it’s got to be the most fun you can have with your clothes on . . . That’s what it looked like.

1. THE TRIP OUT

Straightaway it was obvious that there is something special about carrier operations. The reaction of anyone on the base who discovered that you would be flying out made that clear. “Oh, you’re going out to the carrier,” involuntary grinning. “Oh, yes, you’ll really like it – you’ll have a great time,” wistfully looking out of the window, “yes, it’s really nice” Just by revealing that you’re going to share something of his personal, private and privileged world you have brightened up the day of a two-year desk-jockey – and he’s the one who’s not going. Only nice people react like this. It continued:

“I don’t need to tell you guys, but when you’re on the deck watch out. Those propellers can turn you into boloney real quick: I’ve seen it – it’s not pretty.” The prospect of a trip in one of his aeroplanes has turned the COD (carrier on-board delivery) squadron commander, slim and dapper in his whites, into an expert stand-up man. After a safety equipment double-act with the loadmaster, including the chat about hanging on to wallet and watch when we catch a wire, he reassures us; “Don’t worry, you won’t actually need that stuff. It’s completely safe, you won’t get wet . . . if you do; I lied.” Perfect timing. He’s having fun; so are we.

We flew out in a Grumman C-2A Greyhound, one of those chunky twin turbo-props with lots of fins. With the radar mushroom on top this becomes the E-3 (Hawkeye). Our captain was a tall, round-faced, quietly affable commander with an Italian name like Corleone, and Carl Schofield’s silver hair.

L to R. Mrs Yule. SFO Tony ‘The Adj’ Yule. SFE Dave MacDonald. 4 of Admiral Jack Ready’s relatives, self, Commander Coriolis

“I only allow the best, most experienced, and reliable pilots to fly passengers to the ship,” the admiral had said. Commander Coriolis radiates cool common sense and good judgment. He could work for us any day. A schoolboy dressed in the same gear – dark blue flying suit with garish badges, green Mae West and a red and white painted bone-dome – got into the right-hand seat. I wonder if he has a handle? – ‘Killer’ Carruthers or something?

On the way out we took it in turns to have a look up front. . . . ninety five miles? . . .this thing must do about 200 knots. . . .about half an hour? I elected to be last: it worked. “There’s the ship,” said the captain, pointing to a huge ship-shaped splodge on the 25 mile range ring. It’s a bit hazy, so he takes us down to 500 feet. The three of us peer forward. The excitement is palpable; ‘tension’ would cover it but wouldn’t be the best word. If anyone can fly a perfect approach and carrier landing it‘s this man; and he knows it. The sea is glassy and the weather’s turning out nice, yet the prospect of making another trap has Commander Ciccone’s gloved hand polishing the throttles as he looks for the ship.

We break through the last bit of scud. “There it is!” says the young lad, pointing slightly left of centre. It is magnificent, grey and huge, wider and more sawn-off at the back than I expected, powering north, trailing a wide boiling white and green wake that stretches back, seemingly unattenuated, for miles. How can something that weighs 95,000 tons go so fast?

This is CVN69, the USS Eisenhower. It looks like a carrier, everyone’s seen one, but the one you are going to live on has a character all of its own. You’re compelled to take a special interest in it, the moment you see it. “Stay up here while I fly around; we can’t land for twenty minutes.” The Commander understands. We rack around on to a tight downwind. A few grey aircraft are parked along the narrow triangle to the left of the touchdown zone, nightstoppers from yesterday. A bit close to the runway? I wonder if they’ll move them before we land? There’s an easy answer to that.

Abeam the stern we start a turn on to finals for a pretend approach (how can I get a go?). As we approach the wake it’s obvious he’s got it wrong – definitely going wide. The ship looks a jumble of shapes and lines. Suddenly everything slots into place. The landing runway slides out of the confusion, plain to see. Everyone knows that carriers have angled decks. Snappy approach judgment has to be able to see a straight line at ten degrees to the line drawn by the ship and its wake. This is thinking man’s flying.

We can’t land yet because the ship isn’t ready; it‘s steaming for wind. Actually there isn’t any wind; so where does it think it can find some? Or, if the wind is calm, why can’t we land now? The ship’s going fast enough. It’s not as simple as that.

Close to the runway?

In fact, the ship is not a ship really, it’s a floating airfield. Even the captain is a pilot, not a sailor. This afternoon the carrier’s job will to become runway 18 with a wind of 190/25. To keep this up for, say, four hours on a calm day at least 100 miles of unencumbered water would be needed to the south: hence the motoring the other way this morning. In twenty minutes the ship will have turned round and be headed south at the right speed; not too fast for the first session – propellers and slow jets. To the minute the numerous functions required for deck-flying will have got their acts together. We’re on first.

Back in my seat I do mental DR while we drone around waiting for wire time. At a constant 100 per cent rpm it’s difficult to tell power changes. This man flies smoothly, and there’s no way of guessing where we are on the approach. The loadie waves frantically – we’re about to make the trap (the ‘adj’ [Tony Yule] and I are well up on this jargon). A flash of shadow as the tower goes past and we’re down and stopping. Four seconds in all. Very smooth and progressive; just quick. This ride is free: I must admit that, at $3500 a Concorde seat, I have done much worse.

Perfect trap position

2. THE CAPTAIN

A hat, nametag and coffee later we climb a dozen steep ladders (no fat people around) to see the captain. He’s a smallish, sharp-looking man with Stumpy’s [Colin Morris] black hair, and we catch him in his left-hand front corner of the bridge, face lined with concern as he tries to unjuggle the logistical tangles of today’s programme. There’s a lot of day flying to get through; six hours’ worth. The wind didn’t show as forecast, perhaps? Have we got enough sea room for this afternoon without running out of our protected area? Then what about tonight? A couple of hours free steaming between day and night flying gives sixty miles to play with, but what of the distance to the airfield? What if at 3am, say, the last kid on his last pass gets a problem and has to try for the beach on what fuel he has left? I’m guessing, of course.

It’s very paternalistic. All aircrew below either the rank of commander or the age of forty seem to be referred to as ‘kids’. On a chinagraph board are the details of all the pilots who will be making their CQs today and tonight. They don’t live on this ship, but the captain knows about them all. ‘CQ’ is carrier-qualifying – base flying at the end of a type conversion course. Minimum requirements six day and four night arrested landings – satisfactory ones, that is. Some of my night simulator attempts had stopped alright, but would have worried a few people. Jubilation from outside at a successful trap with an acknowledgment that it wasn’t perfect: “Guess you put them in the net again”

The captain is in charge of a complex amalgam of air and sea. The air side of this is his major personal concern, but he can’t delegate any of the real responsibilities. One mishap - end of career. Draconian, isn’t it? Utter reliability, where everyone walks feet from danger, requires this motivation.

Ship turning left - at low speed

He’s on the bridge all the time that there’s flying going on. The seamanship side of captaining the floating airport shouldn’t pose too many problems for anyone with a feel for offshore yachting, but there’s no allowance for getting it wrong. “Inertia management, I call it,” said the admiral, “and you have to be careful with the turns. If some kid goes in the water off the catapult and you have to turn to miss him you could have another three aircraft topple over the side. Your water speed and rudder angle shouldn’t add up to more than thirty.” (That’s tough at thirty knots – another tip for the yachtsman.)

“Hi, ya’all! Come on in. Good ta see ya. I’m Bill Cross. How was the flight? We’ve got a whole lot of things for you to see. We want you to feel right at home here – go anywhere you like. If you get lost ask anyone – they’ll help you. Say, I’d be real glad if you folks’ll join me for dinner tonight. Have to alter the time – night flying’s a little later; let’s make it 7.45. Hi Mike, that’s one hell of an airplane you have. Must be fun to fly. I’ve heard your handling stuff is interesting . . .

Captain Bill Cross

They are flying at the moment. No problems yet, but a black line down each side of the number two catapult tells yesterday’s story. A couple of unfortunates, on their first day on a deck in the feederliner with the radar on top, took their first cat-shot with their parking brake on. What a disconsolate 100 mile cross-country to the shore, beached after one trap. Must have spoiled their whole day.

He needs to be aware of what’s going on outside, but as someone alerts him to our presence the captain leaps into PR mode, beaming.

He’s well briefed, done the kiss-the-customer course, working hard at his career; but he really means it. He’s really delighted that we’ve come to see how his navy works. He knows we’ll be impressed. What a nice guy! It’s not just that his CV is imposing - to a flying bus driver it’s devastating. This tour, that tour, test pilot’s school, this evaluation unit, in charge of that test flying course, this and that squadron commander. If the shuttle hadn’t of blown up he would flown it: and he’s got his yachtmaster’s ticket as well. Congratulations Mrs Cross; I think you chose an admiral.

3. THE CATAPULT

After lunch, what with the balmy weather and flat sea a stroll on deck seemed in order. Between the bow catapults, abeam the let-go points, a space can be found which is close to the action, but, in general, clear of it (by a few feet). It wouldn’t be a place to take a mischievous eight-year-old.

At this airfield all the taking off, landing, taxying and parking takes place on the first 1000ft of runway. Apart from the raisable jet-blast barriers the deck is completely unfenced. One feels a little vulnerable at first. Insulated and blinkered by the compulsory ear-defenders, mini bone-dome and goggles (in case a bit of dust gets in your eye and, unable to hear engines you blunder into a catapulting wing-tip, thus needing the mini bone-dome) there’s a distinct feeling that you want to watch your back. It feels like diving with a face-mask when there might be sharks lurking.

Successful landings stop abeam the catapults. A ninety right puts you somewhere behind the number two, or a bit further over and more likely for circuits, the number one slingshot track. As a simulator maestro I know how to do this . . . .

When you know you’re stopping close the throttles and let the wire pull you a few feet back. Get the hook up with the little hook-shaped lever on the right, press the button on the stick and waggle the rudder to engage the nosewheel steering; a handful of power to get the machine moving and turning – the next aeroplane is hoping to land forty seconds behind you. At the same time flaps up and wings fold (on the left just behind the throttles). Follow the marshaller (the aeroplane corners as easily as a supermarket trolley). A little group of rubberneckers in front of the Bubble (that’s us) moves just out of the path of your truncated wingtip. Ninety right, then ninety left lines you up on the catapult track. Edge forward exactly in the middle. Kneel the nosewheel leg with the switch on your left knee panel. Unfold the wings - set takeoff flap - correct trim - check the holdback by powering up against it a little - then full cold power, up to the gate - engines OK, a flamboyant salute towards the Bubble – pure theatre. Head back against the seat - a few seconds wait then thump; you’re off. Two seconds later bonk- and the quickly-accepted smooth 4g takeoff roll feels as if it has stopped in its tracks. It’s remarkable how quickly the brain reprogrammes itself. No, you’re not dead in the air. You’re climbing away, ten degrees nose up, 150kts showing and accelerating fast. A 1:1 thrust to weight ratio in cold power - much more than a light Concorde - but it feels as if you have stopped. Maybe one gets used to it.

Hornet has disappeared. Fly 1 looks for the next customer

On deck the watchers are enveloped in a blanket of spent, greasy steam, instantly taking them back to the days of pounds, shillings and pence. What an unexpected association of historically separated technologies; the steam train and the shipboard jet fighter. A sense of smell is our most primitive and powerful remembering device – along with the instinct to jump if a shape moves; inherited from reptiles. It’s all relevant here – what a wild scene. Top Gun didn’t do it justice.

4. THE COLOURS

The men who organise this moving around, loading and shooting are a big part of what makes for the special nature of carrier flying. To watch them at work and figure out two things – why they enjoy it; and why they are so good at it – is an object lesson in homespun psychology; anthropology? sociology? common sense? Call it what you will – it shows you what is going wrong with the development of civilisation (living in towns) and the way it deals with the human beings whose lives it insists on organising. Compulsory protection from cradle to grave, whether you want it or not. Many who need it don’t get it.

I met Tom Cruise on our aeroplane one day, after he had made Top Gun. “What those guys do out there is dangerous,” he told me. He obviously believed it; I think he was quoting a line from the film. He was referring to the flying, though the work on deck cannot be separated. He wasn’t quite right. He should have said that it could be regarded as dangerous, but ought to be remarkably safe if the hazards are universally recognised, and the risks accepted and managed.

The men who work on deck manage a risk-filled environment with great reliability and aplomb. They enjoy it because their contribution towards the well-being of their colleagues is manifestly evident. They’re needed in an obvious and satisfying way – hunter-gatherers working as a team.

Two groups catch the attention first; the catapulters and the safety men – those who give each aeroplane a quick DI as it lines up and prepares to zap down the deck. Smart-looking sailors in seven-folded bell-bottoms? Not exactly. Grubby jeans and squidgy-soled jumping boots are the order of the day. A coloured sweatshirt and float-coat indicate the specialisation. The safeties wear dirty-white with a green cross on the back. Watch them swing into action.

First they swing on the slats, pulling up to look on top of the wing. They smack the flaps, rattle the gear doors, punch the panels on the engines, shake the tail – generally check that the previous landing has not rendered the machine unsuitable for future flight. The additional protection provided by a pair of stout gardening gloves is clearly essential, but this vigorous walk-round needs special care - the engines are running at takeoff power at the time.

The catapulters wear green. Two of them are on intimate terms with the nose-wheel. It obeys every gesture of the front man as he gently cajoles it up to the shuttle (a giant version of the thing that carries the bobbin of weft across the warp. Here it tows the aeroplane along the deck). A subtle flick of the wrist is answered by an obediently collapsing oleo, and a barely perceptible flutter of the hand trundles the little towbar into the slot at the shuttle’s leading edge. A grandiosely elegant Nureyev slide of the arm and leg forward towards two kinds of wide blue indicates that the catapult may take up slack – no longer confidential; quite balletic. For a demo ask our flight engineer, Dave Mac: ‘take it away, maestro.’

Meanwhile greenshirt 2 has been scrambling behind the nosewheel, connecting the holdback link and hooking the other end into a choice of slots in the deck. One end of this rod affair snaps when the total forward forces of catapult and takeoff thrust exceeds its calibrated strain – a function of the mass of the particular aircraft type. It’s important that it doesn’t let go prematurely. “As soon as I get the signal that it’s connected I like to carry about seventy per cent against it to make sure it’s holding,” the admiral said. The holdback man is the last to leave before takeoff. Long after the engine wind-up signal, and alone under the fuselage, he returns his head to the nose-wheel bay to make a final check – then he follows his colleagues out from underneath in short order. Those intakes and propellers are awfully close: great boloney potential.

Despite appearances the nose-wheel does not have a mind of its own. It obeys the catapulter through the medium of the man in the yellow shirt, standing abeam the cockpit. Don’t call him a ‘marshaller’; he wouldn’t like it. This yellow college of aircraft directors includes men of all sorts and conditions, most of them graduates from the ranks of chockers and chainers. Many of them are those fabled micro-marshallers who demand that you put yourself over the edge of the deck, and succeed in parking you like a sardine in a tin. A carrier in full commission may have a hundred aircraft to accommodate; you have to see it to appreciate this use of space.

Aircraft Director

Kneel the nose leg, or unfold your wings?

This master coordinator directs and communicates like the conductor of a chamber orchestra; understated but accurate. There can be no misunderstandings if a flawless performance is to be achieved – and it must be. Imagine the consequences of those little slip-ups, mistakes, so beloved of apologetic training systems. “Was that full power, or unfold the wings? Let’s try full power.” Or: “I wonder if we’re hooked up or not? I expect we are.” This sort of thing can’t happen here.

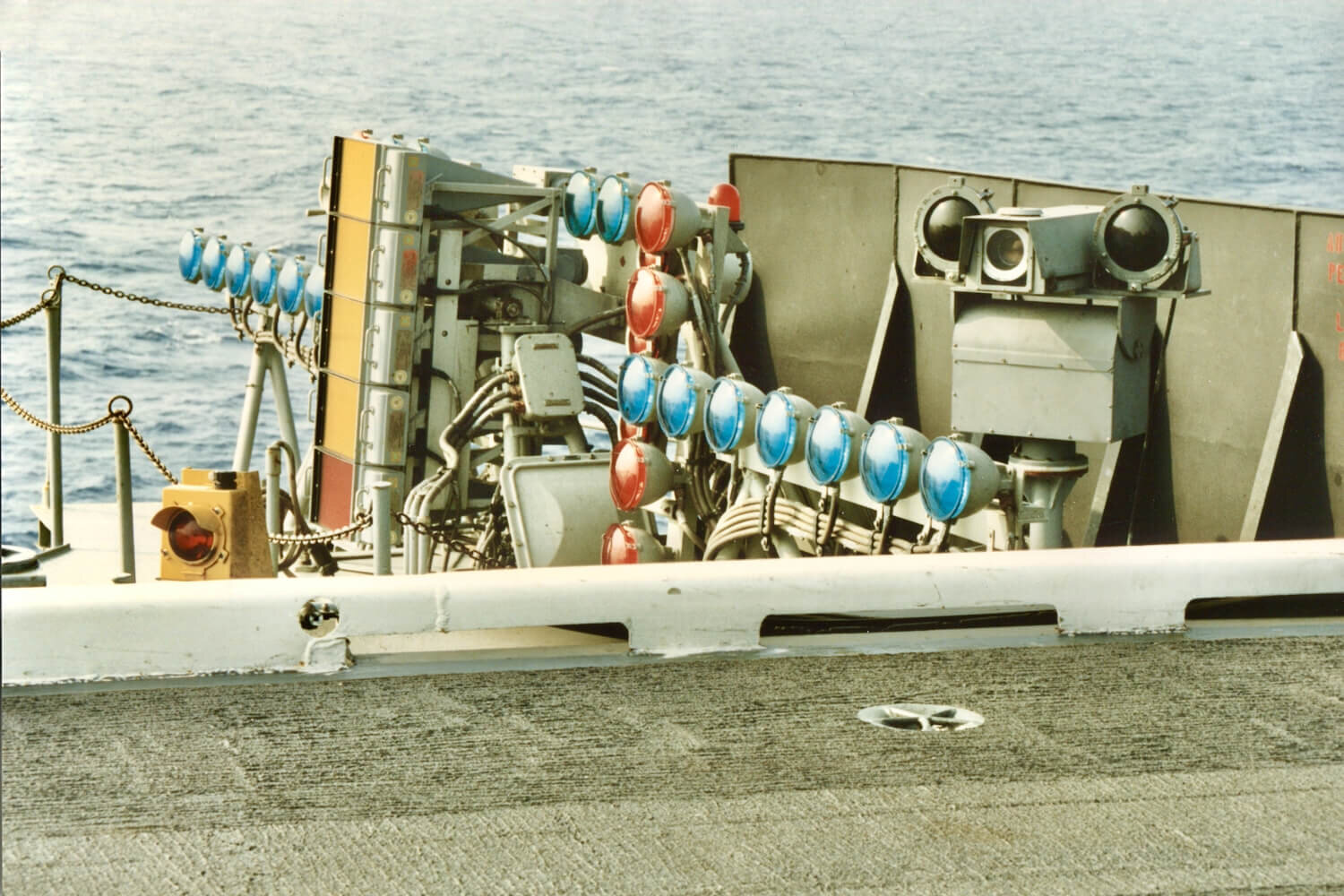

Whites, greens, yellows and a purple (fuel)

It’s all done by sign language: normal conversation is not possible; just lift your ear mufflers to check out the cataclysmic noise (leave the ear-plugs in). The general ambiance is distinctly cool. When unoccupied with the action on the deck little groups of greens, whites, yellows etc. sit in conspiratorial packs in odd corners, much as you might imagine bored kids around the bottom steps of a derelict apartment building in a bad part of town. Here they pose no threat to the passer-by. They don’t look for trouble – just field it with as much economy as possible. (Try strolling across the deck behind a taxying jet; while pretending it doesn’t exist: it’s harder than it looks – the leaning-sideways-into-the-desert-wind mime.) What do the other colours do? If you ever get the chance, go aboard and see. There are seven in all.

Dave MacDonald checks the point five gun crew

5. THE TRAP

There’s a break while a new set of performers comes on. It gives us time to grab an obligatory coffee and doughnut and re-emerge – this time with only the earplugs for protection – at the LSO (landing signal officer) platform. Abeam a point just downwind of the wires, this is the traditional place from which to criticise approaches. Beneath the grating a very blue Atlantic glides by sixty feet below, and instead of a net there’s a sloping trampoline into which to jump in the case of poor tracking. It disappears somewhere under the deck. I instinctively measure the distance to it: this place has an exciting feel about it.

Above, a number of Tomcats and Hornets make leisurely racetracks, the quiet and sober nature of their flying conserving fuel, of course, but signaling strongly the interest being taken in the ship, and the importance that will attach to a reliable performance. One hot-shot does indeed fly down the dead side with wings back, but this is no Top Gun pass; just a tiny suggestion of a wry grin at circuit height. He knows he’ll make it.

Upwind, on the skyline, a multi-coloured Birnam Wood approaches. The deck is being walked to check for foreign objects, like a police hunt for clues. This is a serious matter here. “If you lose your name-tag or something let us know; we’ll stop the flying until we find it.”

With the runway clear and everyone ready the time has come. The first aeroplane is abeam us and starting to turn finals as the spotter with the binoculars bawls something about aircraft types and hooks. No one appears to take any notice, but this information is of interest to the arrester gear people in their deafening hydraulic mill below the deck.

We’re more interested in the approach itself. In landing configuration 4,000 pounds per hour per engine (read on a tape instrument – left knee panel) and thirty degrees of bank should take you from 600 feet downwind, round the turn in a gentle descent, and on to the slot (ball) at three quarters of a mile and 300 feet.

Approach slope indicator

Power at 3,000 pounds a side is about right for the last bit – a four degree approach on the mirror sight, with angle of attack displayed on the coaming in a kind of similar way . . . amber circle - on speed; above it a green ‘go down’ chevron, meaning too slow, and below it a red ‘come up’ one, meaning too fast – upside down traffic lights. If it was my job I would have the logic hacked – I think! The end result is an approach on the T-bar VASI at 135 knots.

From our little spot on the terraces the first attempt looks snappy; plenty of bank and a close-in straighten-up has put him in the right place. It looks a bit shallower than four degrees to me – more like a normal three degree slope – but the man in charge of this end of the proceedings is taking a real interest. He talks rapidly into his telephone with a barrage of helpful advice: “Power – less power – wings level,” and so on. Judging by the sound effects (like sitting in the back of a Trident) and the way the machine rises and falls on its smoky jet-blast the pilot is way ahead of him.

As well as a good eye – and the ability to fly an aircraft while facing backwards, like model radio control (the approach chief judge is an experienced carrier pilot himself, of course) – the LSO has a direct read-out of the angle-of-attack information; clever really.

Three lights on the nose-leg repeat the colours seen in the cockpit; runaway traffic lights with a preponderance of amber. Shooting around the target maybe, but averaging in the right place. Everyone seems satisfied as the Tomcat roars past us at head height and thumps into the deck. Bang-roar: it rushes down the ship, off the bow, and into the air, showering us with hot air and rubber dust . . . no hook? “They make a couple of touch-and-goes first to get the snakes out of the cockpit,” explains a flying suited pilot standing next to me.

No hook, touch and go to settle in

Actually it’s quite crowded on this small rectangle. As well as those who need to be present there are a number of people who have various interests in the afternoon’s action: fellow learners, teachers, prospective squadron colleagues? I don’t know.

Friendly crowd on the LSO platform

But there’re all such awfully nice, polite, well-educated, well-turned-out helpful chaps, delighted that we’re getting in their way and asking stupid questions. We could be hundreds of miles from 47th street Photo. We are hundreds of miles from 47th street Photo. This is a different America – part of what they came over here to create.

The shortness of the final approach matches the smallness of the target. From our position close to the firing-line it is easy to see any deviation from the ideal path, and, just like reading contest aerobatics, the pilot’s psychology transmits itself as if by telepathy. Most approaches are settling down to consistent traps; the all-electric Hornets looking more solid in technique. The Tomcats keep you more on your toes, rocking their wings as they sort out the slipping and skidding that go with bank overcorrections, while the string on the nose flails across the bottom of the windscreen.

Tomcat touches down

One of them still has his hook up and rivets the attention as he makes a wild sixty-degree-steep pull through the centreline, nose high and slowish. It seems to be that problem with the wake and the landing deck direction. The coach goes at his phone hammer and tongs, trying to get the man aboard and salvage a vestige of self-confidence. “Power! Wings level! Less power!” He’s going to hit the tower! “Left!” Now he’s coming straight at us; I edge for the side – no harm in being the first to decide; you could be the only correct one. The nose is high and there’s an absence of smoke. “Power! (I should say so!) Wave-off!” As he starts the last phrase the flying machine sinks visibly. Actually there’s no gap between the two instructions and the Tomcat roars directly over our heads. He isn’t getting any better and a brief chat with the men upstairs decides the inevitable; back to the beach – probably a career move. Like Wotan reluctantly furloughing his favourite daughter the admiral explains later: “I can’t have him on the ship if I can’t trust him.” Best of the best? Kind of looks like it. No doubtfuls; total reliability; no problems. Sleep-easy training. It seems to work.

6. THE BUBBLE

Bubble

There is another interesting place on the deck (or, mostly, beneath it); the Bubble. Like the top of a flying saucer it pokes up between the catapults, and its green armoured-glass windows provide a wrap-around view of the bow launches, like a 360 degree cockpit. It’s a strong little place – capsule really – and it disappears into the deck at the touch of a button if the action gets too wild outside. The windows and roof provide good insulation, and the quiet and cloistered atmosphere inside complements the job that is done here.

The catapult officer sits quietly at his console like a friar in his cell. He has an ascetic’s pale and bony face. His short, dark hair thins on top like a tonsure. At a small desk are spread his mathematical tables and launch record sheet. To each side are arranged the controls for the two bow catapults. When the button is pressed whatever’s attached will leave the ship at the speed dialed in the relevant window. It’s irrevocable. Talk about life in their hands! An immediate and strong sense of destiny accompanies each decision to press the FIRE caption. This is calm and collected work; he never gets it wrong.

To show that he’s one of the ‘if it moves’ team he wears a yellow jersey; it say Cat Off, or something. But his patrician features and well-pressed drill trousers suggest that he has less street time and more desk time than his foredeck colleagues. Out of context you’d never guess that he’s another experienced fighter pilot, a lieutenant commander in his thirties. He’d have been lucky to land a part in the celluloid Top Gun; probably doesn’t even like volleyball. But when it comes to a choice of who you would like to have fly on your wing, or, in particular, shoot you off the ship, Maverick and Iceman would provide little competition. (To be fair they do have some years to go – this man’s at the top end of kid status.) He’s happy for me to crowd alongside to see what happens.

The first skill required is that of aircraft recognition. Alright, I’m sort of joking, but it’s important that the post-graduate expert retains his credibility. “It’s a Devastator B model dash two.” “How do you know it’s a dash two?” Maybe the question is one of genuine enquiry, but it comes from the preproom assistant sitting behind us. He doesn’t want to be difficult, but he’s a back-up who checks for simple errors, makes sure that nothing is overlooked, another memory, another set of eyes. The monitored cat-shooting system. I’m sure it works.

We’ve chosen the correct table for the aeroplane, read off the wind-down-the-deck, and all we need now is the takeoff weight. Outside, a green-shirted catapulter shows an overgrown cash register read-out to the pilot and, having got the nod, walks over and gestures it at our window.

Pilot to confirm takeoff weight

It says 53,000. Ye Gods! Does this itty-bitty single-seater weigh 25 tons? Apparently so; and we come up with an answer off the chart: 136Kts, dialled up, confirmed and committed to the machine like inserting an inertial position. The details are logged in case there’s any feedback later . . . “I didn’t like my second shot today . . catching fish” . . that sort of thing.

Meanwhile the Hornet is alongside us straining at its leash, trying to blow the jet-blast barrier down. The pilot chops his hand down from the top of his helmet and points straight at us, willing us to an eye-to-eye contact. “That’s the salute, okay; you got it, didn’t you?” comes over the footlights. “Saaalut!” The catapult officer announces this first critical point in a declamatory way, like an elongated Gallic greeting; just a confirmation to himself and his assistant that they both saw it. The second critical point follows soon after. He patters a litany of checks that leads up to the pressing of the red square plastic caption. “Slats, speedbrakes, hook, guys out of the way, deck ahead clear, let’s go!” For an instant the fighter hunches, nosewheel tyres squashing; then it’s off like a dragster. Two seconds later the catapult piston runs into its water stop at 136 knots, sending a shudder down the deck. The Hornet is gone.

It happened so fast, and the deck is so instantly transformed – now flat and empty – that your sense of reality feels strained. Did you imagine it? Was there really an aeroplane out there? Do the past and future exist? Perhaps the present is the only reality, suggesting that cat-shots are, for most of the time, creations of the fevered imagination. What a surreal way to take off. Fantastic.

A Tomcat taxies up on our left. It’s a two-seater of course, they all are, but who might be in it? Could the man in the back be an instructor? Almost certainly not. There is virtually no instructional flying on to the deck. Firstly, this is very much look-after-yourself aviation, and, secondly, you would be hard pushed to find an instructor who’d risk it. The general drift of the naval pilot’s attitude goes something like . . “If there’s to be any landing on decks I’m going to drive and I’ll be sitting in the front; otherwise I’d be delighted to offer every advice from the ship.”

Anyway, this aeroplane can’t be a two-stick trainer; it has two names on the side. It’s the fighting mount of Lieutenants Flatley and Mazanowski. The real Flatley and Mazanowski are elsewhere today. Perhaps they’re on leave; did they fly their trusty machine in the Gulf? I wonder what ship they were on. Maybe they’ve gone their separate ways in advantageous career moves. Is it Lieutenant Commander Mazanowski? Was Flatley such an ace at flying Tomcat 112 that an uninterrupted line of green tags leaps out at you from the landing scoreboard – straight to test pilots’ school . . even Topgun? We’ll never know.

We do know that their impersonators have satisfied the LSO with their touch-and-goes, come to terms with the snakes, and made a successful trap. The taxying across the deck and on to the number one catapult is a little tentative, much to the chagrin of the West Side Story cast who wave frantically, letting their exasperation hang out. “How can these expensively educated college kids be so slow?” One man throws his gloves to the deck in frustration. Don’t even start to explain; there isn’t much sociology here worth studying, but everyone likes to be involved in a snappy job.

We’ve got their takeoff weight, checked the wind, watched them come up to the shuttle, greenshirts scrambling around the nosewheel. Mazanowski doesn’t have much to do - but he has to be there. He wriggles about in his seat, trying to find the comfortable powerless-passenger position. His hands play conspicuously on the coaming. Who’s kidding who? He’s mentally measuring the distance to the handle between his legs: it might be his most useful control.

The barrier is up, the helpers are scrambling about the bits and pieces. In the humid air a couple of soft white vapour ropes snake down the deck and climb vertically into the engine intakes, just ahead of the holdback checker. Flatley is running at takeoff power, and we look for a salute. He’s staring at us through his sunglass visor, but his hands are down. His painted-up bonedome is rotating slowly and very deliberately from side to side. ‘Tension’ would now be a very suitable word with which to describe the atmosphere. Something is wrong: he doesn’t want to go. Are we going to launch him? He daren’t throttle back until everyone’s sure of what’s happening. Our man presses CANCEL and talks to someone. Outside, the head yellowshirt with the wands waves throttle-back and we breath again.

What next? (“Don’t screw up Flats – I see two buckets and mops with our names on them”). Flatley and Mazanowski confer. There’s some radio chat Someone in the tower offers advice - maybe it’s just the gauge. Another expert tries to help - if the rpm’s okay it’s the transmitter, perhaps; have another go. Everyone offers advice - have another go.

So we’re back in business. Flatley gets the wind-up signal, and Mazanowski looks as if he’s getting electric shocks from his seat. Of course nothing has changed and Flatley does the right thing – shakes his head, waits for the signal, closes the throttles, gets unhooked and goes off to get chocked and chained. He’s a good pilot - you can tell. At least he’s got them aboard, 112 has not been put at risk, Mazanowski didn’t have to jump on his first cat-shot, they’ve brought their nightstop kit and, who knows, maybe tomorrow they’ll get the perfect circuit session – a flat sea and everyone else finished; the ship to themselves.

Tomcat 112 as Flatley left it

7. AFTER DINNER

After dinner we watched some night flying from the John Wayne deck of the bridge – top floor, one above the captain. It’s deserted because an admiral is not required for a training trip. You can even sit in that armchair-on-a-pole, master of all you survey. It’s a wonderful place for pondering the nature of existence. The sea is completely calm (as far as this large ship is concerned) and the sky completely dark – eight eighths overcast. There is no visual reference whatever, nor any sensation of motion, even though the carrier is cruising at twenty knots. We are floating in a dimensionless world of black – that’s what it feels like. It is institutional life at its best: orderly, predictable, sometimes difficult, interdependent, good food and a lot of fun.

This was my first visit to a working warship; yet, from the moment of stepping on the deck I felt a sense of déja vu. There was something quite familiar about the ambience of the place: it was like school, partly.

I went away to school when I was eight; hated every minute of it. Ten years of boorish philistine tyranny. This may be a slight overstatement – the particular establishments that were my home from eight to eighteen were relatively benign as the system goes; not exactly Tom Brown’s Schooldays – but they exemplified the anachronistic, backward-looking British attachment to traditions that were developed to support a privileged Establishment (at what cost?); and demonstrated how certain British attitudes towards the way we should treat each other have survived, little changed, while elsewhere societies have tried to evolve to suit the changing circumstances that those with foresight and imagination could see around them.

It is obvious that the US Navy retains much tradition of its historical forebears. Books about Nelson, his tactics and seamanship, and just about every aspect of British naval life from Drake to Jutland provide bedtime reading at the admiral’s house. The Norfolk Naval Museum has many detailed exhibits describing battles and skirmishes that were part of the ex-colonists’ early history. Some of the storylines were confusing: ‘ . . after several sporadic engagements with the French ships the British were unable to secure a foothold in the bay, and Admiral Smith (or Jones) decided to return to New York for the winter. It was a significant victory. .’ Winter tied up in New York? Victory? Then the penny dropped. We were the bad guys. Of course, they came over here to get away from an entrenched system that they could see was unfair and unjust, but too dense and dangerously overgrown to change. Do we suffer it still? Yes and no. Has the American experiment worked? Perhaps the answer must be the same.

“I like America,” cabareted Noel Coward. He didn’t like it all – but he did like the enthusiasm, openness and friendliness that come from a conscious attempt to live up to the nation’s stated aim that everyone has a right to a share of satisfaction and respect. It seems logical to assume that aboard this ship intangible but convincing evidence of this fresh start could be sensed. The Navy is a branch of American life which grows directly from the two and three hundred year old limb of the transatlantic tree. Maybe this is why we felt welcome and at home here; difficult to put your finger on it really.

It wasn’t exactly like school; it was how school should have been. Either that, or, forty years too late, I was old enough to go.

8. NEXT DAY IT WAS OUR TURN

Just kidding!